Gothic Architecture and Sexuality in the Circle of Horace Walpole by Matthew M. Reeve

Author:Matthew M. Reeve

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The Pennsylvania State University Press

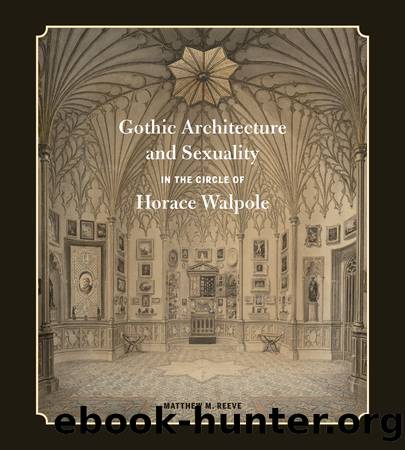

Fig. 99 Thomas Holloway, âContrasted attitudes of a man and a fribble.â From Lavater, Essays on Physiognomy (1789), 3:213.

In Delanyâs 1768 commentary on the Priory, âfribbleâ has a different range of meanings. Focusing on the mirrored surfaces of his libraryâsomething that was relatively new to the English interior and therefore worthy of commentaryâshe too characterizes Batemanâs house and its illusionistic surfaces as a double, or a second self. The stylish, pretentious, and effete surfaces of the man and the building become synonymous; these surfaces act like a veneer that exists independently of a hidden inner self, which Delany clearly derides, even if she has called him âour friendâ and has emulated his Chinese designs.107 Delany provides a queer interpretation of an eighteenth-century trope of the mirror in which the âsubject becomes artificial by overinvesting in the [mirrorâs] image: the subject disappears behind the character he produces and takes pleasure from himself as he would from a realized fiction.â108 The mirrors, in other words, are understood to reflect not Dicky Bateman, but his âfribbleâ persona. Unfortunately, we know much less about the original appearance of the room than we would like, but mirrors were certainly dominant ornamentation in it, since mirrors or âlooking glass[es]â were also noted in the contemporary account in Windsor and Its Environs, which confirms that the library was âin the Chinese Taste, which, by Means of Glasses, [gave] a double Reflection.â This suggests that the mirrors were, like those of the famous Villa Palagonia in Sicily or the slightly later mirrors from Robert Adamâs Northumberland House of circa 1773â74, integral components of the wall surfaces rather than hanging mirrors in the Chinese style, such as those by Chippendale or Ince and Mayhew.109 More directly relevant to Old Windsor, many of the villas built along the Thames employed the newly affordable mirror in their interiors and used them similarly to guide or even distort vision.110 In the library, books were not read, mirrors usurped the role of painted and graphic representations, and the multiplied human subject became the image for meditation and analysis (more so perhaps than the books, to follow the drift of Delanyâs critique).111 Mirrors were central to Batemanâs design of the interior spaces of the Priory: elsewhere he toyed with optical illusion and manipulated its spatial properties, including âWindows [mirrors] . . . so contrived as to shew the Company on their Heads,â thus suggesting the use of concave mirrors to provide inverted, anamorphic images of their subjects.112 In its style and in its fictive, unreal surfaces, Batemanâs house literally and figuratively inverted contemporary nostrums of English decorum.

Paralleling a perverse architectural interior with a perverse or morally corrupt character, Delany suggests that if the surface of the mirror could expose Batemanâs inner character, it might âshew him his own insignificancy.â Just as the beautiful face of Oscar Wildeâs Dorian Gray disguises his real, inner character (displaced to a painting), so are the surfaces of the Priory and the mirrors in particular doubles that fail to signify a morally or sexually corrupt inner self.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Technical Art History by Jehane Ragai(232)

The Slavic Myths by Noah Charney(190)

Drawing Landscapes by Barrington Barber(176)

Simply Artificial Intelligence by Dorling Kindersley(166)

Drawing for the Soul by Zoë Ingram(160)

The Art of Painting Sea Life in Watercolor by Maury Aaseng Hailey E. Herrera Louise De Masi and Ronald Pratt(151)

Compacts and Cosmetics by Madeleine Marsh(149)

The Art of Portrait Drawing by Cuong i(149)

Preparing Dinosaurs by Wylie Caitlin Donahue;(141)

Egyptian art by Jean Capart(136)

A text-book of the history of painting by Van Dyke John Charles 1856-1932(129)

Winslow Homer by Shibutani Baku(124)

Pollak's Arm by Hans von Trotha(123)

Through Japan with Brush & Ink by Chiura Obata(110)

Botanical Illustration by Valerie Price(106)

Culture and Ideology under the Seleukids by Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides Stefan Pfeiffer(106)

Pornoterrorism: De-Aestheticising Power by Louis Armand Jaromir Lelek(106)

Jane Evans. Chinese Brush Painting. A Complete Course in Traditional and Modern Techniques by Unknown(96)

Medieval and Renaissance Fashion by Raphaël Jacquemin(94)